I was going over online training materials for my new part-time gig at Monkeypod Kitchen when I found out how Peter Merriman got famous. In an old PBS interview, he told the reporter that he was washing dishes one day at Merriman’s Waimea – his first restaurant, which opened in 1988 – when a server told him there was a customer who wanted to speak with him. At the time, Merriman’s – now a household name in Hawai’i – was struggling to survive. Peter was washing dishes because he couldn’t afford to hire a dishwasher. “I’m busy!” he called out to the server. The server returned a minute later. “He insists,” he said. The customer was none other than Johnny Apple, the famous New York Times food writer known for his insatiable appetite and encyclopedic knowledge of food, wine and fine dining throughout the world. Apple loved what Merriman was doing, sourcing locally-grown ingredients in a time when hardly anyone in Hawai’i had ever heard of farm-to-table. Upon returning to New York he published a story about his discovery on the Hawaiʻi Island and the rest is history.

On Tuesday I joined a dozen other Monkeypodders at the Honolulu Fish Auction just after the sun came up. Monkeypod Kitchen, part of Handcrafted Restaurant Group owned by Peter Merriman and Bill Terry, works with Fresh Island Fish, the only seafood distributor on Oʻahu sharing a dock with the fish auction. Our sales rep John gave us a tour of their companyʻs facility as well as the auction.

Fresh Island Fish operates 25 out of the 120 commercial fishing vessels that come in and out of Honoluluʻs pier 38, where the auction resides. The boats go out for two weeks at a time and return to this location to unload their catch. The auction, which has been operating six days a week since 1952, sees 65,000-75,000 pounds of fish every morning on average. The morning we were there they received 100,000 pounds. Men in rubber boots, reflective vests and hoodies swarm the dock with pallet jacks and dockerʻs hooks moving fish from boats to ice to inside the auction and back out again to load onto trucks or pass through customs. Most of the buyers, such as Fresh Island Fish, are local, but a few are from Japan. It is their job to distribute Hawaiʻi fish throughout the archipelago and the rest of the world.

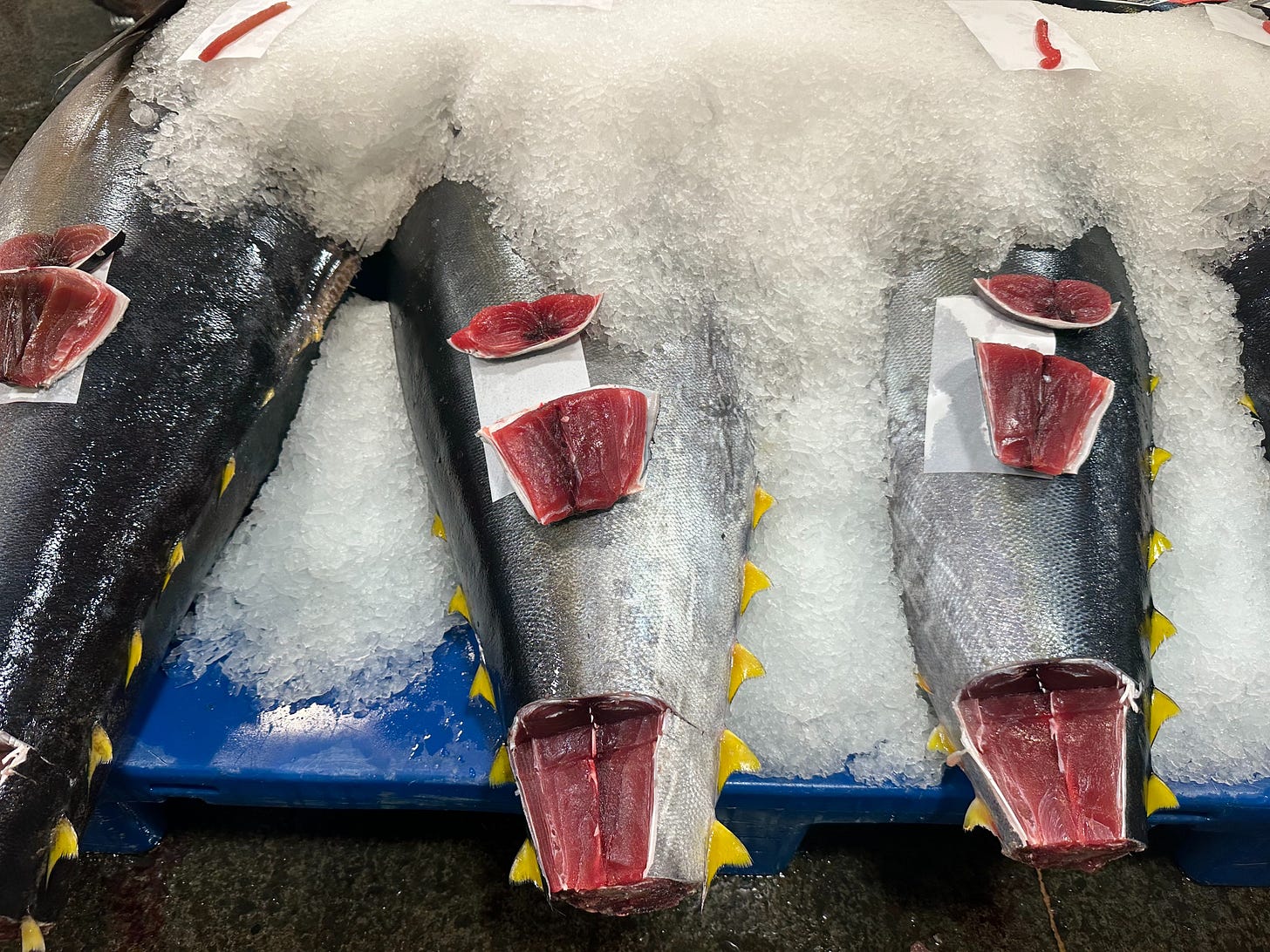

Inside the auction, a dozen guys move from fish to fish with the auctioneer. Mostly they are bidding on tuna, although there is also a small percentage of mahi mahi and swordfish as well. Pallets of new fish come in as fast as they go out. Each time they arrive someone will be there to lay a piece of white paper on top of them, so the guy behind him can have a place to lay the core sample he is about to take. Meanwhile another guy is slicing a portion off the tail to flip over, so buyers can see the color variances in the flesh. (I know I’m being exclusive by only using the words he and him, but besides some women touring the facility I only saw men.)

Buyers are also looking at the condition of the fishʻs eyes, which boats brought them in and how long they were out at sea. While bright red sashimi-grade tuna is prized there is also a need for less expensive lower quality, or “fry grade,” tuna, depending on how the restaurant will prepare it. The color of the fish is determined by a variety of factors including the age of the fish, what they were eating, the temperature of the water and the location where they were caught. When a buyer wants to bid on a fish they will make a hand gesture to the auctioneer. If they win, they drop their tag on the fish and the fish is theirs.

The Honolulu Fish Auction is modeled after Tsukiji Market in Tokyo and is the only tuna auction of its kind in the U.S. While the unfortunate reality is that commercial vessels from countries like Philippines and China take more than its fair share out of the ocean, Hawaiʻi has the most highly regulated fishing laws in the world. Its fleet is certified by the Marine Stewardship Council, an international nonprofit which serves to prevent overfishing and ensure sustainable fishing practices, and each vessel has observers from NOAA Fisheries whose job it is to make sure rules are being followed at all times to ensure safe handling, sustainability and healthy ecosystems and that each boat is staying within their designated boundaries.

A restaurant of Monkeypodʻs size serves over 1000 guests a day. Purchasing fish from smaller day boat fishers who prioritize hook-and-line methods is not an option. Luckily, Hawaiʻi’s longshore fishing industry is one we can trust.

Itʻs cool that San Diego allows those boats to do that! I donʻt know what the regulation in Hawaiʻi is for direct sales. The closest thing we have to that on Oʻahu is Local Iʻa and Forage Hawaiʻi, which source from local day boat fishers.

Thanks Ellen! Now you know where Hawaiian fish comes from!